The Zen of Pricing Models

Not all models are equal

This publication is broken up into three sections:

TL;DR - For those wanting a quick take

Summary - For those wanting a bit more context and high level points

Article - Main body of work containing full detailed article and explanations that you might want to consume over several readings

TL;DR

Everyday goods and services have a “price” or a “price tag.”

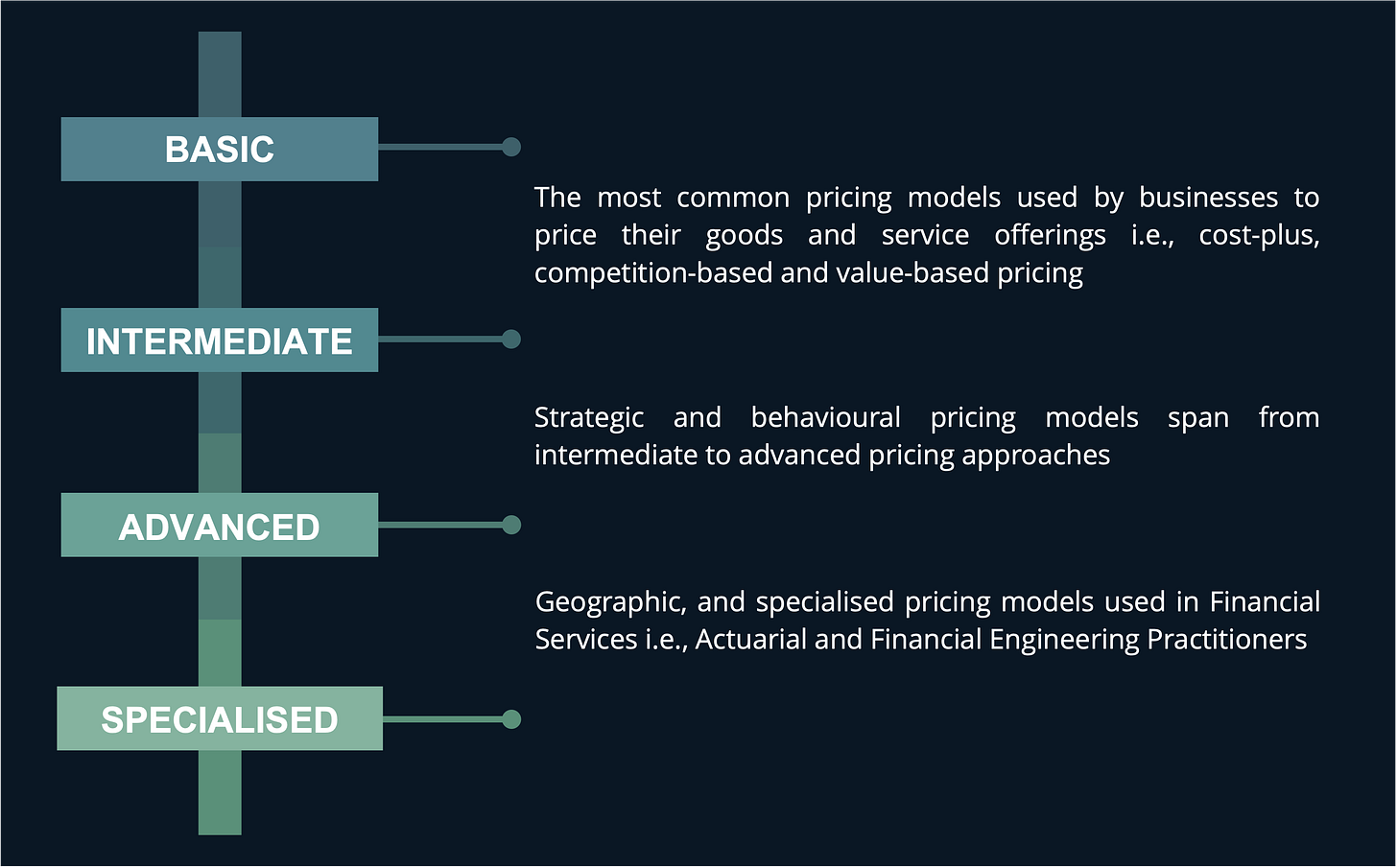

There are numerous pricing models. I have grouped them into a few thematic areas.

Standard pricing models:

Cost-plus pricing models

Competitor-based pricing models

Value-based pricing models

Non-standard pricing models:

Strategy informed pricing models - (i.e., Auction, Freemium, High-Low, Pay-per-Use, Penetration, Skim, Two-dimensional and Volume-based pricing models),

Behavioural pricing models - (i.e., Bundle, Fees-at-risk, Nonlinear, Multi-person and Psychological pricing models),

Temporal pricing models - (i.e., Dynamic, Hourly and Project-based pricing models),

Location-based pricing models - (i.e., Geographic-based pricing models),

Specialist pricing models - (i.e., Actuarial and Financial Engineering pricing models),

High risk pricing models - (i.e., Customer-based, Flat rate, Pay What you Want pricing models)

Despite having well-defined pricing models, there are times when there can be what is termed as revenue leakage. There are many ways to address revenue leakage.

The link pricing has to both business and product strategy is unmistakable and if businesses were to focus their time and energy to getting their pricing right the benefits would exceed cost cutting effiency exercises by a wide margin.

Summary

Everyday goods and services have a “price” or a “price tag.” The prevalence and importance of pricing can be missed given how various industries charge their ‘customers’.

Insurance companies do not talk about prices; they talk about their “premiums,” a seemingly genteel and harmless term. The taxes, fees and surcharges we pay to governments and public authorities are prices that at their best pay for high quality, shared public goods and services ranging from trash removal to schools to healthcare facilities to driver license issuance and inspections.

We pay other prices for the use of highways, bridges, and tunnels frequently in the form of tolls. In the accommodation space people who do not own property pay rent and those that borrowed to acquire property pay mortgages. Banks have prices in the form of interest rates and non-interest revenue captured via fees or “schedules of charges”.

In most large value purchases the list price is not the final price. In business-to-business transactions, most prices are negotiated. Most employees don’t think about the price they charge for their contribution to the company they work for.

There are numerous pricing models. I have grouped them into a few thematic areas.

Standard pricing models:

Cost-plus pricing models

Competitor-based pricing models

Value-based pricing models

Non-standard pricing models:

Strategy informed pricing models - (i.e., Auction, Freemium, High-Low, Pay-per-Use, Penetration, Skim, Two-dimensional and Volume-based pricing models)

Behavioural pricing models - (i.e., Bundle, Fees at risk, Nonlinear, Multi-person and Psychological pricing models)

Temporal pricing models - (i.e., Dynamic, Hourly and Project-based pricing models)

Location-based pricing models - (i.e., Geographic-based pricing models)

Specialist pricing models - (i.e., Actuarial and Financial Engineering pricing models)

High risk pricing models - (i.e., Customer-based, Flat rate, Pay What you Want pricing models)

Despite having well-defined pricing models, there are times when there can be what is termed as revenue leakage. This comes about due to a variety of reasons like not having a defined pricing process with clearly stipulated governance controls.

Once you know the areas where your business is likely to leak revenue, you can prepare an action plan to prevent these leaks before they can cause any lasting damage to your business.

The link pricing has to both business and product strategy is unmistakable and if businesses were to focus their time and energy to getting their pricing right the benefits would exceed cost cutting effiency exercises by a wide margin.

Article

“[T]his thing called ‘price’ is really, really important. I still think that a lot of people underthink it through. You have a lot of companies that start and the only difference between the ones that succeed and fail is that one figured out how to make money, because they were deep-in thinking through the revenue, price, and business model. I think that’s underattended to generally.” – Steve Ballmer - Be all-in, or all-out: Steve Ballmer’s advice for start-ups. The Next Web, March 4, 2014

The ‘prices’ all around us

My last article spoke about the connection between product packaging and pricing.

This article will just go a bit deeper into discussing specific pricing models. At many companies, a lot of effort is spent on finding cost cutting optimisations from day-to-day operations.

As mentioned in my previous article, pricing is one of the highest leverage levers that a business can use to boost earnings.

Everyday goods and services have a “price” or a “price tag.” The prevalence and importance of pricing can be missed given how various industries charge their ‘customers’.

Insurance companies do not talk about prices; they talk about their “premiums,” a seemingly genteel and harmless term. Lawyers, consultants, and architects have fees or receive an honorarium. Private schools charge tuitions.

The taxes, fees and surcharges we pay to governments and public authorities are prices that at their best pay for high quality, shared public goods and services ranging from trash removal to schools to healthcare facilities to driver license issuance and inspections.

We pay other prices for the use of highways, bridges, and tunnels frequently in the form of tolls. In the accommodation space people who do not own property pay rent and those that borrowed to acquire property pay mortgages.

Other examples of prices include broker commissions. Banks have prices in the form of interest rates and non-interest revenue captured via fees or “schedules of charges”.

In most large value purchases the list price is not the final price. In business-to-business transactions, where most prices are negotiated, suppliers and middlemen see “price” as a battle on many fronts.

Using the list price at best as guidance or starting point, they negotiate over terms and conditions, such as discounts, payment terms, order minimums, and on-invoice and off-invoice rebates.

This discussion on pricing would not be complete without mentioning how employees are compensated, the term “compensation” clouds the nature of the transaction between employers and employees.

Most employees don’t think about the price they charge for their contribution to the company they work for. Some of the terms forming part of the hidden veil are salary, wage, bonus, or stipend. As an aside payments to employees are usually the most significant part of any employers cost base.

The take-away from the above examples is that prices are common in a market economy and generally the principle market clearing mechanism.

You could say it is a trusim that price and value are not the say thing.

In Lady Windemere’s Fan, Oscar Wilde had Lord Darlington quip that a cynic was ‘a man who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing.’

The above quote is timeless in describing the challenge of the concepts of price and value.

Pricing for Porsche Cayman product launch

The Porsche Cayman product launch exemplifies the power of positioning, product packaging and pricing.

The following excerpt is taken from Confessions of a Pricing Man written by Hermann Simon.

“Should a company follow established industry practices when it chooses the price position of a new product? Not necessarily. More relevant than traditional industry practices or rules is the true understanding of a product’s perceived value. The following case of the Porsche Cayman underlines the key role of the value to customer for the price positioning. The Cayman S is a coupé based on the Porsche Boxster convertible. At what price should Porsche launch the Cayman? The automotive industry had its own clear, experience-based answer: the price of the coupé must be roughly 10 % below the price of the convertible. At that time, market data showed that coupés were indeed 7–11 % less expensive than convertibles. Because the Boxster’s price was €52,265, standard industry practice would call for the price of the Cayman to be around €47,000.

The CEO of Porsche at that time, Wendelin Wiedeking, decided to buck that industry trend. A big fan of value pricing, Wiedeking wanted to get a deeper understanding of the Cayman’s value to customer. He asked us to do a very thorough global study which revealed that Porsche should do the exact opposite of what conventional wisdom said. The higher-than-expected value of the Cayman was driven by a mixture of factors, including the design, a stronger engine, and, of course, the Porsche brand. The Cayman’s price should not be 10 % less than the Boxster’s price, but rather 10 % higher. Porsche followed our recommendation and launched the Cayman at a price of 58,529 Euros. The new model became a big success, despite the higher price. Once again, a deep understanding of value to customer proved to be the foundation for an appropriate premium pricing strategy.”

With this context and story let’s get into examining pricing models in detail.

Deep dive into pricing models

Without wasting time let’s get into understanding some of the pricing models that organisations are using.

There are a variety of pricing model approaches. Instead of sharing a laundry list of pricing models I have grouped them into thematic areas.

Standard pricing models

Most common pricing models

Competition-Based Pricing

Competition-based pricing is also known as competitive pricing or competitor-based pricing. This pricing strategy focuses on the existing market rate (or going rate) for a company’s product or service; it doesn’t take into account the cost of your product or consumer demand.

Instead, a competition-based pricing strategy uses your competitors’ prices as a benchmark. Businesses who compete in a highly saturated space may choose this strategy since a slight price difference may be the deciding factor for customers.

With competition-based pricing, you can price your products slightly below your competition, the same as your competition, or slightly above your competition.

Cost-Plus Pricing

A cost-plus pricing strategy focuses solely on the cost of producing your product or service, or your COGS. It’s also known as markup pricing since businesses who use this strategy “markup” their products based on how much they’d like to profit. To apply the cost-plus method, add a fixed percentage to your product production cost.

Value-Based Pricing

A value-based pricing strategy is when companies price their products or services based on what the customer is willing to pay. Even if it can charge more for a product, the company decides to set its prices based on customer interest and data. If used accurately, value-based pricing can boost your customer sentiment and loyalty. It can also help you prioritize your customers in other facets of your business, like marketing and service.

Non-standard (exotic) pricing models

Strategy-informed pricing models

Auction Pricing

One of the oldest forms of price setting are auctions. Auctions come in many forms, each designed to fit a particular situation or challenge.

The Internet has helped drive the usage and appeal of auctions. The most widely known example is eBay. The highest bidder wins the auction on eBay, but they pay the bid of the next-highest bidder plus a small differential. This is almost identical to an auction process already used by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe around 1,800.

He would sell his manuscripts to the highest bidding publisher, who would then pay the price of the second-highest bidder. Columbia University professor William Vickrey proved that it is optimal for a bidder in these auctions to reveal his or her maximum willingness to pay. He won the Nobel Prize for this fundamental insight in 1996 and that form of auction now bears his name.

Google uses a clever auction system for selling advertising space, which takes into account the utility of the ad for the search-engine user as well as the willingness to pay of the advertiser. Google also provides the advertisers key data on advertising efficiency. The system was developed by the renowned economist Hal Varian, who has been Google’s chief economist since 2007.

In auctions the idea is normally to extract the maximum willingness to pay from the bidder. For public contracts, other goals can take precedence, such as ensuring the financial viability of the participating companies, securing energy supplies, or avoiding capacity constraints. In order to achieve such goals, economists develop special “market designs.”

Freemium Pricing

A combination of the words “free” and “premium,” freemium pricing is when companies offer a basic version of their product for free hoping that users will eventually pay to upgrade to access more features. Unlike cost-plus, freemium is a pricing strategy commonly used by SaaS and other software companies.

They choose this strategy because free trials and limited memberships offer a peek into a software’s full functionality — and also build trust with a potential customer before purchase. With freemium, a company’s prices must be a function of the perceived value of their products.

High-Low Pricing

A high-low pricing strategy is when a company initially sells a product at a high price but lowers that price when the product drops in novelty or relevance. Discounts, clearance sections, and year-end sales are examples of high-low pricing in action — hence the reason why this strategy may also be called a discount pricing strategy.

High-low pricing is commonly used by retail firms that sell seasonal items or products that change often, such as clothing, decor, and furniture.

Pay Per Use Pricing

The traditional price model is that one buys the product, pays its price, and then owns and uses the product. An airline buys jet engines for its aircraft, a logistics company buys tires for its trucks, and a car manufacturer installs a painting facility, buys paint, and paints its cars.

Taking a needs-oriented perspective (i.e., job to be done approach) creates a totally different basis for setting prices. The needs of the customers often do not warrant owning the product; they would rather have the benefit, the performance, and the needs fulfillment that the product provides.

An airline does not have to own jet engines for its aircraft. It needs thrust. Similarly, the trucking company needs the performance of the tires, and the car manufacturer needs a painted car.

Instead of charging a price for the product, a manufacturer or supplier can charge a price for what the product actually does. That is the basis for innovative pay-per-use or pay-as-you-go price models.

Penetration Pricing

Contrasted with skim pricing, a penetration pricing strategy is when companies enter the market with an extremely low price, effectively drawing attention (and revenue) away from higher-priced competitors.

Penetration pricing isn’t sustainable in the long run, however, and is typically applied for a short time. This pricing method works best for brand new businesses looking for customers or for businesses that are breaking into an existing, competitive market.

Premium Pricing

Also known as prestige pricing and luxury pricing, a premium pricing strategy is when companies price their products high to present the image that their products are high-value, luxury, or premium. Prestige pricing focuses on the perceived value of a product rather than the actual value or production cost.

Prestige pricing is a direct function of brand awareness and brand perception. Brands that apply this pricing method are known for providing value and status through their products — which is why they’re priced higher than other competitors. Fashion and technology are often priced using this strategy because they can be marketed as luxurious, exclusive, and rare.

Skim Pricing

A skimming pricing strategy is when companies charge the highest possible price for a new product and then lower the price over time as the product becomes less and less popular. Skimming is different from high-low pricing in that prices are lowered gradually over time.

Technology products, such as DVD players, video game consoles, and smartphones, are typically priced using this strategy as they become less relevant over time. A skimming pricing strategy helps recover sunk costs and sell products well beyond their novelty, but the strategy can also annoy consumers who bought at full price.

Two-dimensional Pricing (Fixed + Variable)

Two-dimensional and multidimensional price systems are commonplace. In industries such as telecommunications, energy, and water supply, prices regularly consist of a fixed base price and a variable price based on actual usage.

In the case of industrial gases, which are sold in steel containers, there is a daily rate for renting the bottles, and a price per kilo for the gases. A customer who uses one bottle of gas per day therefore pays less per kilogram than a customer who takes 10 days to use up one bottle. In spite of offering the same scheme to each customer the actual price paid strongly differs significantly according to usage intensity: a very smart scheme for price differentiation.

Volume-based Pricing

The most common form of volume-dependent price differentiation is the volume discount. The more someone buys, the higher the discount, which means that the customer pays a lower price per unit.

For volume based pricing, prices scale based on usage metrics (e.g., number of accounts, number of users, number of transactions).

With volume discounts, the devil is in the detail. The result depends on how the volume discount is structured.

There are essentially two forms of volume discounts:

full-volume - The full-volume variant means that the discount rate applies to the entire purchase volume

incremental discounts - The incremental rebate means that the discount rate applies only to the incremental volume, and not the full volume

Behavioural Pricing Models

Bundle Pricing

A bundle pricing strategy is when you offer (or "bundle") two or more complementary products or services together and sell them for a single price. You may choose to sell your bundled products or services only as part of a bundle, or sell them as both components of bundles and individual products. This is a great way to add value through your offerings to customers who are willing to pay extra upfront for more than one product

When a seller packages several products together and charges a total price less than the sum of the individual product prices, it is called price bundling. Bundling is a very effective way to differentiate prices.

Bundling pricing strategies aim to shift buyers to choose buying a bundle offering over buying single products.

Satellite TV is the one industry where bundling is popular, you buy bundles of TV channels. Generally, no consumer is keen to buy individual TV channels and to perform financial analysis to make sure their consumer surplus remains intact.

Fees at-risk Pricing

Fees at-risk model – This is an example of pricing model where a vendor is willing to take on risk with a client. Typically fees received are a % of the final value capture based on agreed upon markers for validation (e.g., validated by the client client’s finance or analytics team based on analysis of performance). This sort of model is used mostly within a B2B context.

For a model like this to work a business would need to break out their model into a base charge essentially to cover some overhead costs then create a series of milestones that will unlock further fees. The final fees to be unlocked are based on performance and part of the upside value capture that a customer experiences. If there is no upside for the customer there is no additional value sharing.

The closest analogue of a fees at risk model in a B2C context in the retail market can be seen with a money-back guarantee. Typically there is limited upside for the merchant (i.e. sale price) and likewise limited downside for the consumer.

Nonlinear Pricing

A nonlinear pricing schedule refers to any pricing structure where the total charges payable by customers are not proportional to the quantity of their consumed services. Non-linear prices are prices that vary depending on the amount of consumption by the customer. An example might be a water tariff, which has higher per litre prices for higher levels of consumption than for lower levels of consumption.

Non-linear prices are like multi-part prices in that they allow the operator to charge prices at the margin that reflect marginal cost, while using the inframarginal prices to manage earnings. Inframarginal prices are the prices charged for units that are not at the margin.

Multi-person Pricing

Multi-person pricing means setting a price for groups of people. The total price will vary by the number of people. Travel agents make offers which allow partners or children to travel at reduced prices or for free. Airlines sometimes will let a second guest or a partner fly at half-price or free. Some restaurants will charge half-price for a dish if one person pays full price.

Something which doesn’t fall under multi-person pricing is the situation when consumers themselves bundle their demand, in order to press for a bigger discount.

Psychological Pricing

Psychological pricing is what it sounds like — it targets human psychology to boost your sales. For example, according to the "9-digit effect", even though a product that costs $99.99 is essentially $100, customers may see this as a good deal simply because of the "9" in the price.

Another way to use psychological pricing would be to place a more expensive item directly next to (either, in-store or online) the one you're most focused on selling. Or offer a "buy one, get one 50% off (or free)" deal that makes customers feel as though the circumstances are too good to pass up on.

Temporal Pricing Models

Dynamic Pricing

Dynamic pricing is also known as surge pricing, demand pricing, or time-based pricing. It’s a flexible pricing strategy where prices fluctuate based on market and customer demand. Hotels, airlines, event venues, and utility companies use dynamic pricing by applying algorithms that consider competitor pricing, demand, and other factors. These algorithms allow companies to shift prices to match when and what the customer is willing to pay at the exact moment they’re ready to make a purchase.

Hourly Pricing

Hourly pricing, also known as rate-based pricing, is commonly used by consultants, freelancers, contractors, and other individuals or laborers who provide business services. Hourly pricing is essentially trading time for money.

Project-Based Pricing

A project-based pricing strategy is the opposite of hourly pricing — this approach charges a flat fee per project instead of a direct exchange of money for time. It is also used by consultants, freelancers, contractors, and other individuals or laborers who provide business services.

Project-based pricing may be estimated based on the value of the project deliverables. Projects also are time bound i.e., they have start and end dates for deliverables to be delivered.

Location-based Pricing

Geographic Pricing

Geographic pricing is when products or services are priced differently depending on geographical location or market. This strategy may be used if a customer from another country is making a purchase or if there are disparities in factors like the economy or wages (from the location in which you're selling a good to the location of the person it is being sold to).

Specialist Pricing

Actuarial Pricing

Actuarial pricing refers to the process that actuaries use to determine the most effective price to set for an insurance premium. Actuarial pricing involves assessing the potential risk of insuring clients and finding the price ranges that can accept this risk while still generating a profit. Unlike valuation, actuarial pricing relies on the probability of a loss occurring when covering a client's policy claim. Additionally, actuarial pricing helps insurers establish policy premiums that can account for any losses from an associated financial risk. This also ensures companies can provide payments to policyholders when they make claims.

Financial Instrument Pricing aka Financial Engineering

Financial engineering is the use of mathematical techniques to price financial instruments, for example debt instruments like bonds, equities or ‘equity’ like instruments such as preference shares or derivatives like forwards, futures or options.

A range of specialised knowledge and techniques are used to price these instruments.

High risk pricing models

Customer-driven Pricing

Whether it is called “ name your own price”, “customer-driven pricing”, or “reverse pricing”, the process rests on the hope that the customer will reveal his or her true willingness to pay. The price offered by the customer is binding for him or her, and payment is secured because the customer must supply a credit card number or allow their account to be debited. As soon as a customer’s offer exceeds a minimum price threshold (known only to the seller), the customer gets the product and pays the offered price.

Flat Rate Pricing

Flat rate is the modern term for a lump-sum price. Flat rate pricing could be a subscription model that charges users a flat fee per month or year for all features and all levels of access.

A customer pays one fixed price per month or per year, and can then use the product or service as much as he or she wants in that period. Flat rates are very widely used today in telecommunications and Internet services. Cable or satellite television subscribers generally pay one flat rate per month to gain access to all available channels and watch them as often as they like.

Flat rate pricing means having a consistent price per unit regardless of the amount purchased. Another example, if you subscribe to a newspaper like the New York Times, you pay a fixed rate per month or year.

Pay What You Want Pricing

The “pay what you want” model takes customer-driven pricing one step further. Under this model, the buyer determines the price, but the seller is obligated to accept it. The music group Radiohead released its album In Rainbows online in 2007 with a “pay what you want” model. The album was downloaded over one million times, with 40 % of the “buyers” paying an average price of $6 apiece. Occasionally one will see a restaurant, hotel, or other service business try a similar approach. After finishing the meal or checking out, the guest pays whatever price he or she wants to. From a pricing standpoint, the seller is entirely at the buyer’s mercy. In such situations, the seller may indeed see a certain number of customers pay prices that cover costs. Other customers will take advantage of the opportunity to pay little or nothing.

Undermining your pricing and long-term revenue growth

Despite having well-defined pricing models, there are times when there can be what is termed as revenue leakage. This comes about due to a variety of reasons like not having a defined pricing process with clearly stipulated governance controls.

Below I list some areas where you could have revenue leakage. Many on- and off-invoice items can easily lead to price and margin leaks. Here I provide a non-exhaustive list:

Annual volume bonus: an end-of-year bonus paid to customers if preset purchase volume targets are met.

Cash discount: a deduction from the invoice price if payment for an order is made quickly, often within 15 days.

Consignment cost: the cost of funds when a supplier provides consigned inventory to a wholesaler or retailer.

Cooperative advertising: an allowance paid to support local advertising of the manufacturer’s brand by a retailer or wholesaler.

End-customer discount: a rebate paid to a retailer for selling a product to a specific customer—often a large or national one—at a discount.

Freight: the cost to the company of transporting goods to the customer.

Market-development funds: a discount to promote sales growth in specific segments of a market.

Off-invoice promotions: a marketing incentive that would, for example, pay retailers a rebate on sales during a specific promotional period.

On-line order discount: a discount offered to customers ordering over the Internet or an intranet.

Performance penalties: a discount that sellers agree to give buyers if performance targets, such as quality levels or delivery times, are missed.

Receivables carrying cost: the cost of funds from the moment an invoice is sent until payment is received.

Slotting allowance: an allowance paid to retailers to secure a set amount of shelf space.

Stocking allowance: a discount paid to wholesalers or retailers to make large purchases into inventory, often before a seasonal increase in demand.

Managing Revenue Leakage

Revenue leakage is not something any organization – be it a major enterprise or a startup – can afford to neglect. Once you know the areas where your business is likely to leak revenue, you can prepare an action plan to prevent these leaks before they can cause any lasting damage to your business.

A few examples that can help you curb revenue leakage at your organization are documented below:

Automated systems – By centralizing and automating your processes, you can stop the existing leakages and also prevent such leaks from happening again in the future. When business processes are centralized, automated, and approved in real-time, invoices and timesheets can be sent, monitored, and tracked on-the-go.

Data validations – Adding validation checks across different systems ensures that the data entered is correct. Any failures need to be flagged to the appropriate department on time so that corrections can take place before sending the final invoice to the client.

Real-time visibility & insights – Data analytics helps you track your data and cash flows to find anomalies or detect delinquent transactions. Real-time visibility also helps in tracking accurate resource utilization and efficiency of the team to enhance the customer experience. Furthermore, the time spent on any additional task can be tracked down, adequately planned, and utilized in a much more efficient manner towards project billable time.

Client engagement and transparency – The best way to engage your client is to deliver on all accounts and provide them with transparency. If they are in the loop and understand the work that is getting done, what is the billing to expect and future timelines well, it simplifies overall billing and fewer questions get asked.

Revenue Leakage Audit – No matter how meticulously you have drafted the revenue leakage prevention strategies, you will need to examine and analyze business processes separately to identify and eliminate revenue leakages. That’s where revenue leakage audit can be quite helpful. Revenue leakage audit helps you identify the main source(s) of the leaks and allow you to tackle the challenge in the most holistic manner.

Closing Remarks

This has been a long article and I feel there is no need to re-iterate points from above.

Having a structured approach including system and process to manage pricing is important.

The link pricing has to both business and product strategy is unmistakable and if businesses were to focus their time and energy to getting their pricing right the benefits would exceed cost cutting effiency exercises by a wide margin.

I will close off by saying that pricing is the highest impact lever any business has to drive both topline and bottomline growth.

Post Script

Before you go, please could you do the following?

Subscribe

Share

Survey

Star

If you got value from reading the article a star liking would be highly appreciated

Resources

Auction Theory by Vijay Krishna

Confessions of a Pricing Man by Hermann Simon

Pricing strategy and models by Qualtrics

Pricing strategy guide by Profit Well

Pricing strategy by Hub Spot